REPEAT!

Saṃsāra / संसार (səmˈsɑːrə) | noun– A cycle of reincarnation. Birth| life| death| rebirth. Repeat.

Architect-ist | noun verb – Birth giver, care giver and facilitator of architecture.

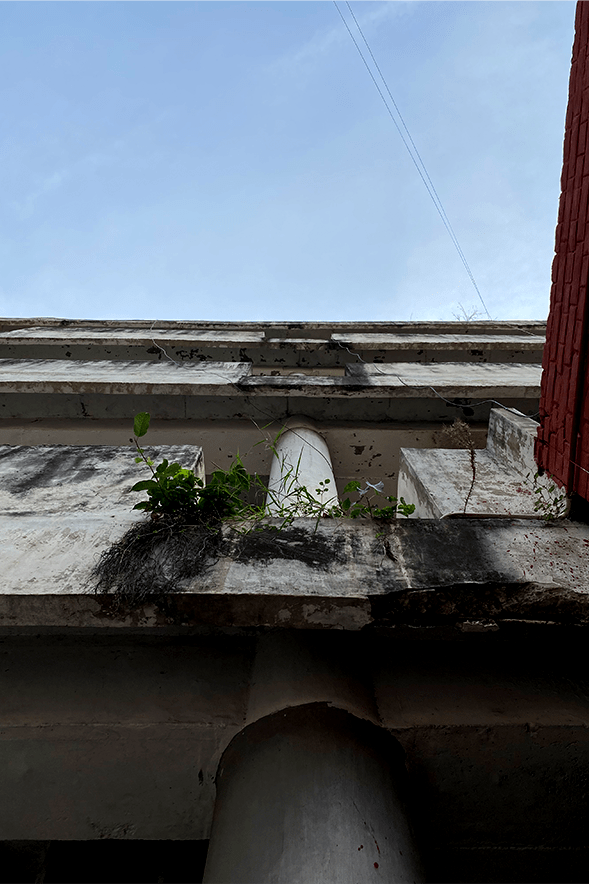

As you walk through the quite lush lanes of Chandigarh towards the monumental Government Fine Art Museum, it is as if the time stands still in front of this crippling, grimy and yet strikingly Corbusien vision of utopia (or more like the museum of eroded “utopia”). It is as if you have become a little mechanical part of Corbusier’s magnanimous industrial machine. Looking at the sculptural masses of concrete scattered around in the museum compound; one might blush seeing the naked sturdy finish of raw concrete buildings standing arrogantly. But, Chandigarh has become a modernist ruin but unlike the romantique Roman ruins– it is a display of the graceless ageing and decay of the modern city envisioned as a symbol of Independent India.

Much like elastic skin which wraps itself over the metabolic tissue of life and bones, buildings and cities are wrapped by the life around it. The human bodies decay daily at a imperceptible pace, but the body’s “materiality” is built to adapt to this decomposition, and also to facilitate its growth and changes throughout its life, maintaining the vessel until its graceful demise. Modern Buildings on the other hand are typically planned for 50 years maximum, falling into a rueful decay thereafter. The decay is ugly, the wrinkly crack in its concrete is which cannot be looked at with admiration, as it slowly turns into an old shell with no use.

What happened? You look awful.

How old do you think I am?

You look as beatdown as an ambassador car.

Offf. That’s brutal. Well, I am meant to represent the modern machine man or used to at some point. Only if plastic surgery was an option.

While cities are growing, the metamorphosis can be seen as a sign of vigour but there comes a point, where the building fulfils its original function, then what happens? Typically, they are euthanised by the bourgeois to begin again but more likely, left alone to rot and slowly die, in neglect. This gradual expiration is a painful visual erosion of memories for the mourners who were once its vigorous occupants.

In the age of the Anthropocene with global crisis imminent, there is a need for architects to redefine Architecture and the professional practice in a circular fashion instead its traditional linearity. With climate change, financial uncertainty, population boom there is a clear loss of land and with this inevitable change, existing buildings, and future new buildings will have to prepare and adapt to this impediment.

A resilience must be sown by its maker, the architect who will have to redefine his role in the life span of the building and not just until its delivery.

We must let go of this Linearity in our practice, which is followed starting from the early stages of design typically engulfed by budgets and “Pinterest” ideas to choosing the cheapest or glitziest materials as commanded by the clients and then finally the lack of control or involvement in its realisation while engulfed by the political and cultural ideologies at that moment in time. The architect is so removed from the process that it often feels like the profession has become like a surrogate mother whose job has become to only deliver the child. This detachment of the architect from its craft is a cry for architects to become bricoleurs, become makers of montage. (Scalbert, 1996)

To illustrate and emphasize some questions on the role of an architect and the linear progression of architecture let’s turn to the design and construction of Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh, with the grim background of India and Pakistan painful partition during Independence, northern states of India – Punjab and Haryana needed a new capital that represented Indian values and new future. The new nation that was grappling to find its own identity, Chandigarh was born with a vision to represent a utopian society (Urban Planning/utopian dreaming. Idealistic and “modern” in its functionality, brutalism was the style in fashion. Removed from the culture and traditional reference points, Corbusier exploited concrete to achieve his vision. In-situ concrete enabled him to create a raw, stripped back naked city that was strictly functional but sculptural in its mass (Bologna, 2020). One could draw a similarity to the new age advertisement man of the 60s. The design process followed by Le Corbusier was abashingly linear in terms of its initialisation to its realisation, including the copy and pasting done of the “Principles of modern architecture” on an alien site that he only visited four times which has now caused the premature failure of the city.

Even though his vision of the city was based on industrialisation, Chandigarh and its buildings proved to be no well-oiled machines. Culturally detached, this international style was an antithesis of a new city. I hereby declare that Corbusier was arrogant and classicist while designing Chandigarh as he was insensitive to the local context, materiality and more importantly how the buildings would age well after he passed.

Chandigarh is a great example of how important it is for architects to go beyond just their traditional scope of definition as the builder or draftsman, it is imperative that we design buildings that adapt and perform well after we die and live a graceful life.

While no one can determine an expiration date of a building but the imminent death of buildings and its resilience to be repurposed in the future cannot be an afterthought. We as architects and planners need to design buildings and spaces that decompose with grace as the sinews of life change or depart it. The industry NEEDS to move away from aesthetic greenwashing as a tool for pitching their buildings as the perfect baton of sustainability.

The energy and time required to create a new building is enormous, about 38% of total greenhouse gas is generated by the built industry. The “energy” and the waste that comes from the consumption of the materials used has added to the grim era of the Anthropocene (UN Environment Programme,2020). To add to the problem, cookie cutter – mass produced houses that scream ostentatious ignorance and a lack of surface level design intention at best, mc mansions are the perfect example of wasteful “more”. An example of this is the Kunming Sunshine City, where a series of newly constructed buildings were demolished because of low-quality materials, lack of demand, lack of urban planning and demand.

More irresolute buildings and the mind set of quantity over quality leads to a space open for exploitation, crime, and discriminatory spaces. As architects, we have a shared responsibility to make conscious decisions and educate stakeholders that LESS IS MORE (Architecture and the Circular Economy: a pending partnership, 2022). Even though the concept of circular economy and its implementation has been around for a while, its penetration into architecture is still at its fringes, limited to professionals who are environmentally conscious.

There’s beauty in antiquity but not in unavailing shells of memories.

The concept of circularity not only applies to environmental actions at a global level but also to the micro-environment where the intervention of the architect resides. This needs to start from the grassroots, architects need to be more accessible to the real middle class and not just the bourgeois, research needs to be applied to create a more socialist open complex system with identified thresholds that act as indicators for a change, making this system a more adaptive system. The making of Architecture becomes more “bricoleur”, the architect become a “messenger between nature and culture” or a figure of bricoleur reimagining the matrix of this wounded ecosystem of the Anthropocene. (Scalbert, 1996)

Here the architect is the facilitator and not just the maker, there is a need for us architects to be well versed with the economics of building/construction, hence a new definition is required –

New definition

Architect-ist – the new economist who reinforces the relationship between available resources, cultural, materiality and political ideologies and its output materialised in spaces.

The new architect is the birth giver who is not just dedicated to creating the “form/mass” but is the reinforcer who strengthens the design intent in a circular fashion keeping in mind three key points – resilience, repurpose and material sustenance. They are the key executors or general practitioners of building, always involved until death does them apart.

To make sure the Architect-ist has a framework to guide them, Five Points of New Architecture are re written as a toolkit of the 21st century Architecture.

Design with re-purposefulness

More often than not older buildings are deserted by its occupants or discarded completely in its season of grey. So much of Chandigarh is waiting to be reborn with the same vigour it was once created with, but the form is such that it is often more cost effective to begin again. The birth givers are long gone, leaving their creations un-attended and frozen in time, crippling. As creators and wardens of eroding buildings, the Architect-ist is to conscious of the long-lasting impact it can have on occupants well after the architects have passed and therefore it is imperative that any space is designed keeping in mind its ability to morph in the future. From the Knees of my Nose to the Belly of my Toes by Alex Chinneck repurposes an abandoned building in London to comment on the crippling housing market in an artistic impression. Here the building is repurposed to connect and engage the community.

Design buildings that are not a burden.

Design with aging

The new Architect-ist designs for decay right from its seed stage. Although not all decay can be designed for, but Architect-ist can design for anticipated decay. Designing by taking advantage of the biological processes of materials will help cities of tomorrow from crumbling and being abandoned. In Zurich, the demolition rate has increased over a period of 180 years. the new architect-ist is the carer of the decaying urban stock that cares to decrease the increasing mortality rate.

Design circularly

Clay is clay even after a hundred years from now. Today in a global economy there is an opportunity to design buildings driven by micro-economy principles that can help create systems in the built environment that are co dependant. Resilience can be achieved through the practice of circularity. The new Architect-ist will design buildings that are co-dependant machine of different synergised systems.

Design with culture

No more stripped back buildings that can’t be identified which to place it sits in. Buildings that are culturally naked do more harm than good in a secular economy where there is a need to appreciate the culture and the vulnerability of the society. The new Architect-ist is the maker and bringer of culture in its creation.

These five points of architecture becomes a tool kit for the future of architecture, whatever it maybe.

Chandigarh as it still stands today, is a mark of the turbulent yet exciting times of new India in the 1950s. It sits like an old veteran with each crack telling a tale of its time. However, this empty carcass is waiting to be reborn and play its part in the cycle of samsara and it is our duty as the new architects – the architect-ist to be the new obstetricians and undertakers of these buildings. There is an imminent need of the hour that the scope and the role of an architect extends beyond just parametric modelling and form-making, we need to be more involved in research of its site and the molecules that make up the building which ultimately would be the driver of ageing. It is our responsibility to the future occupants of the spaces we create to design for decay, to design for recyclability, to design for repurpose and lastly for culture.